One morning at the beginning of March, I woke up with slight chills. COVID-19 hadn’t yet begun to spread in New York City, so I chalked it up to a cold and went about my normal routine – I took public transit to work, attended meetings with colleagues, and bought groceries for the week ahead.

By the next morning, I had developed a fever and a cough, and my sense of taste and smell had vanished. I wasn’t able to get a test because the few that were available at the time were dedicated exclusively to frontline healthcare workers. However, there’s almost no doubt in my mind that I had COVID-19, and I was horrified to think that I might have spread the virus to others.

In an effort to keep those around me up-to-date, I called my parents, friends, and colleagues to let them know they might have been exposed. I also informed the HR and facilities teams at my office, who sent me a survey about all of the spaces I’d entered, and the people I might have encountered in the two weeks prior to my illness. Despite my best efforts, there were ultimately a lot of gaps and unknown contacts (like people I’d been with on the subway, or other shoppers at the grocery store), as well as details about my own health, that went unaccounted for and left me without a full picture of my situation.

Technology-driven COVID tracking and tracing systems are designed to help close some of the gaps that person-to-person contact tracing leaves open, and are already being used around the world. Some use GPS-based location data or more tightly localized bluetooth data, are compatible with most smartphones, and are more complete than going primarily off memory. When combined with widespread testing, a robust and well-resourced healthcare system, and coordinated governance, the system has been effective, and is credited with helping countries flatten their rates of new infections. South Korea and Singapore are perhaps the best known examples, but dozens of countries are implementing technology-driven approaches to contact tracing with varying degrees of invasiveness.

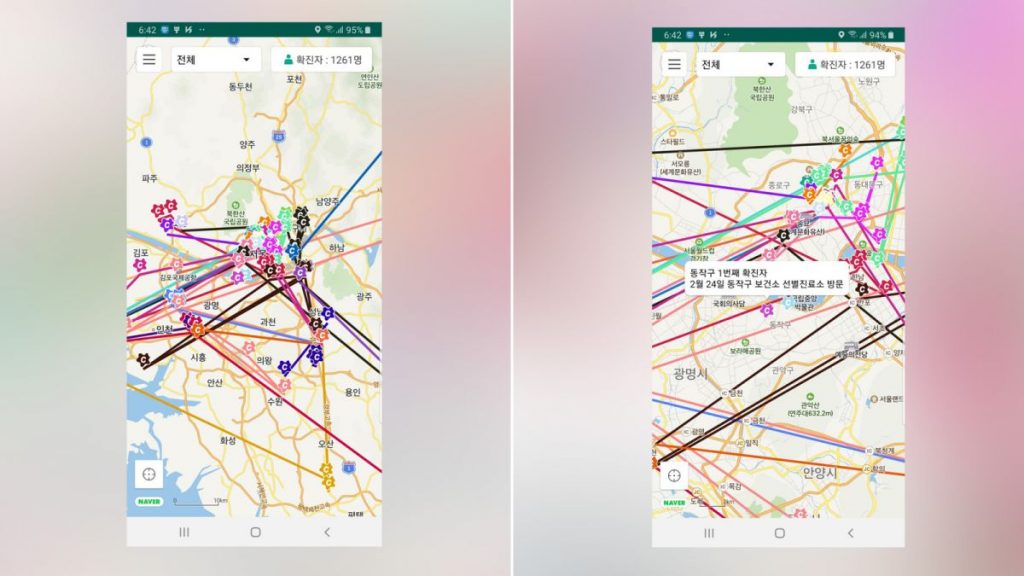

These types of interventions raise a lot of concerns about data privacy, individual rights, and collective public health. South Korea’s coronavirus contact tracing system, for example, uses a combination of credit card transaction data, mobile phone tracking, closed-circuit TV footage, and cell-phone alerts to track known cases and alert the public to the activity and locations of infected individuals. This substantial level of data-monitoring comes at the expense of individual privacy, especially where widely broadcast smartphone alerts are concerned: “The age, gender, and ethnicity of a confirmed case, as well as the district where he or she resides and works, is…included in these public notifications. As a result, it is probable that these individuals can be identified by members of their community.” There have been reported instances of infected people being publicly shamed and harassed online, and the stigma attached to infection is becoming a separate issue all its own.

“The in-the-moment desire to collect information about citizens in crisis can lead to a systemic invasion of privacy that lasts decades,” says Mark Surman, Executive Director of the Mozilla Foundation. As we start to explore more technology-driven options for containing the virus and responding to the pandemic, we also need to balance the public health response with concerns about civil liberties, surveillance, and individual protections.

So how can we use technology and data-tracking to protect the health of our societies without compromising our civil liberties? As the public health response to the spread of coronavirus shifts focus from containment towards long-term mitigation, tech leaders are rolling out tools to help federal and state agencies implement strategies like contact tracing at scale. There are still many open questions about the privacy implications of tools like these, and SFE grantees are developing resources to help us learn more about maintaining a balance between protecting our privacy and strengthening our collective public health. You can use the resources below to educate yourself about what’s at stake, and what you can do to stay safe:

Dive deeper into contract tracing with a webinar on tech, privacy, and civil liberties in the pandemic

The Center for Information Technology Policy (CITP) at Princeton University is a nexus of expertise in technology, engineering, public policy, and the social sciences. SFE supports CITP’s research, teaching, and events addressing digital technologies and the ways they interact with society. On April 16, Dr. Ed Felton hosted a webinar on COVID-19, Technology, Privacy and Civil Liberties, which analyzed the major proposed uses of data and technology in the public health response to COVID-19. The webinar weighs the public health value of technology-driven tracking methods against their implications for individual privacy and civil liberties, and demonstrates that widespread adoption is critical to the efficacy of tracing technology. He concludes that unless the public’s confidence in that technology’s safety and security is high, it’s unlikely that we’ll achieve the levels of adoption needed to put it to use at a meaningful scale.

Hear what leaders in the field have to say about how we can protect personal privacy and enhance public health at the same time

The Mozilla Foundation is one of the foremost organizations working to build a healthy internet. Their work spans a range of privacy-promoting activities, from providing consumers with information about their tech choices, to academic research about internet health. Mozilla Foundation Executive Director Mark Surman recently published a piece on Privacy Norms and the Pandemic that offered a hopeful look at how privacy standards could end up being strengthened by the pandemic. “The current setting may offer a chance for this way of thinking to make a leap forward,” says Surman, “and to nudge governments and tech companies towards the idea that privacy-by-design should be the norm.”

Mozilla Fellow Frederike Kaltheuner also hosted a Twitter chat about the intersections of data privacy and issues accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The chat addressed questions like: Do we have to trade our privacy to protect public health? Are social media platforms profiting from coronavirus misinformation? And, how secure are the video conferencing apps we now rely on? The conversation has been archived here.

Additionally, many organizations beyond the SFE grantee network are collaborating to establish best practices for maintaining individual privacy, and advancing public health during the pandemic – you can learn more about these efforts from guidelines published by EU Member States, the ACLU, and almost 100 advocacy and civil society groups, as well as a frequently-updated tracker of new measures that have been introduced around the world response to COVID-19 and that pose a risk to digital rights.

*****

A technology-driven tracking system would have almost certainly been a lot more comprehensive than what I was able to do. I feel reasonably sure that by the end of my sickness, almost none of my personal data had been exposed or shared without my discretion, but I still don’t know if I contracted the virus from a known contact of mine, or whether I gave it to anyone else. My experience has left many things unknown, and illustrates the urgency of developing best practices for data-sharing that balance advancing our collective public health with protecting personal information from being exposed or surveilled.